Mines, Morale and International Treaties — Will the Ottawa Convention Survive the 21st Century?

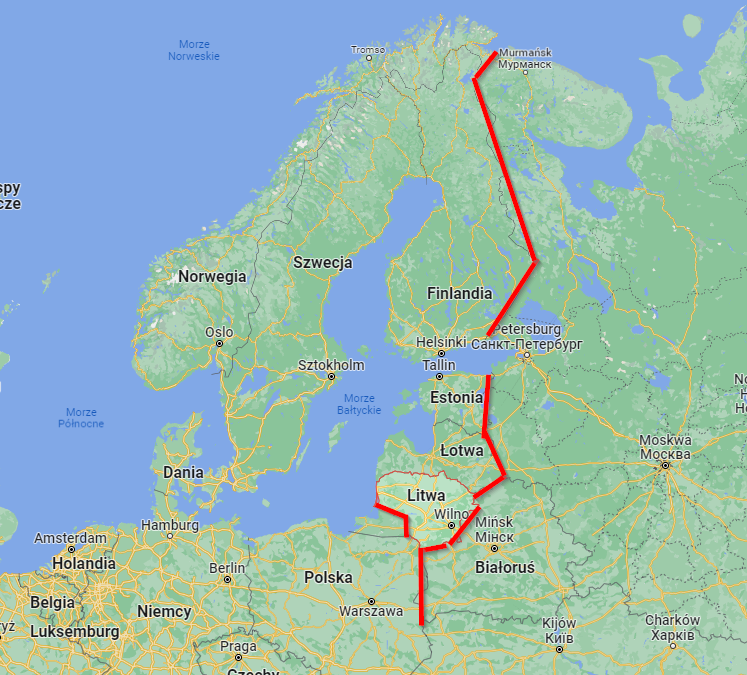

Poland’s, Finland’s and the Baltic states’ decision to withdraw from the treaty banning anti-personnel mines after more than two decades since it came into force represents something more than a turn in defense policy. This is a moment when Europe is redefining the boundary between security and human rights. Are mines returning to the arsenal of democratic states? And what does this mean for the future of humanitarian law?

A Treaty That Sought to End the Era of Mines

The Ottawa Convention — formally the Convention on the Prohibition of the Use, Stockpiling, Production and Transfer of Anti-Personnel Mines — was adopted on December 3, 1997. Its signatories committed not only to ceasing the use of anti-personnel mines, but also to destroying all stockpiles (within 4 years) and clearing their own territories (within 10 years). The treaty entered into force in March 1999, and its effects were spectacular: over 55 million mines destroyed, the complete collapse of the global trade in these weapons, and in some countries — such as Mozambique or Nicaragua — official recognition as mine-free.

From Cambodia to Bosnia — How Did the Treaty Come About?

The impulse for its creation came from the drastic images of the 1980s and 1990s: children in Africa and Asia maimed by mines, farmers in Cambodia dying while tending their fields, women in Bosnia living in fear of stepping onto a mined road. The International Campaign to Ban Landmines (ICBL), which received the Nobel Peace Prize in 1997, gathered the voices of victims and transformed them into political pressure. Canada, under the leadership of Minister Lloyd Axworthy, initiated the so-called Ottawa Process — rapid, informal negotiations that culminated in the signing of the document in 1997.

Princess Diana — A Voice That Brought Global Breakthrough

In January 1997, Princess Diana visited a minefield in Angola — wearing a helmet and bulletproof vest, she walked among the deminers. The photographs went around the world, and HALO Trust emphasized:

“Her visit transformed the perception of mines from a military tool into a global humanitarian problem.”

This event significantly increased media and political pressure — several months later, the treaty was negotiated in Oslo.

Prince Harry — Continuing the Mission

In 2019, Prince Harry walked the same route in Angola, following in his mother’s footsteps. HALO Trust reported new $60 million support from the Angolan government for the demining program. Harry emphasized that

“a world without mines is a moral imperative,”

which took place just before a UN conference aimed at completely eliminating mines by 2025.

Not Everyone Was on Board

From the beginning, the world’s largest military powers did not sign the Convention: the USA, Russia, China, India, or Pakistan. The USA justified this by citing, among other things, the necessity of defending the border with North Korea and the need to use “smart mines” that self-destruct after 24 hours. Russia, meanwhile, possesses — according to 2023 data — the world’s largest stockpile of anti-personnel mines: 26.5 million pieces.

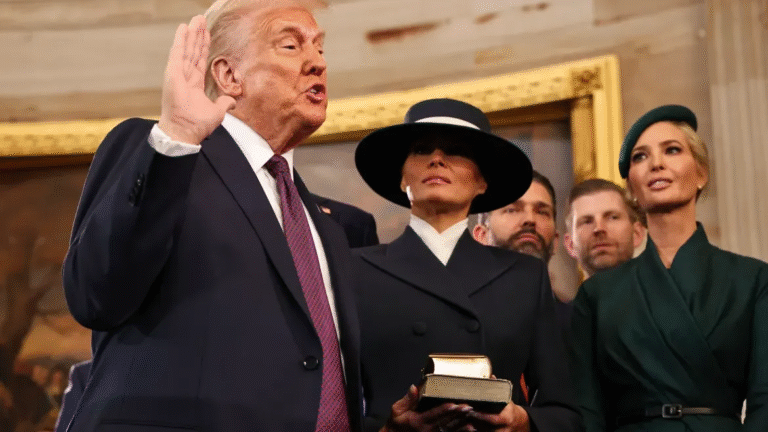

2025 — The First Mass Withdrawal from the Treaty

In March 2025, four NATO states: Poland, Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia, announced their withdrawal from the treaty. Finland joined in April. The reason? Russia — which not only is not party to the Convention but also uses mines intensively on Ukrainian territory. Defense ministers from the region’s states emphasized that:

“in the face of growing conventional and hybrid threats, we cannot afford to give up any tool of defense.”

Prime Minister Donald Tusk stated:

“In our surroundings, everyone we might fear has them.”

Mines — Weapons with the Longest Shelf Life

While their production cost is merely a few dollars, their removal can cost hundreds, even thousands of dollars. It is estimated that between 50 and 110 million mines still lie underground worldwide, and their annual toll amounts to several thousand victims — mainly civilians and children. Case in point? In 2022, Syria recorded 834 mine victims, Ukraine at least 600.

Mines Are Not Meant to Kill. They Are Meant to Wound

One of the paradoxes of this weapon is that most anti-personnel mines were not designed to kill. Their aim is to maim — because a wounded soldier requires transport, care, and resources. Demoralization, fear, logistics — this is a psychological weapon. However, the side effect is civilian tragedy: mines remain active for decades after war ends.

Are They Still Necessary?

According to the International Committee of the Red Cross — no. As early as 1996, it was pointed out that “the military value of mines is minimal,” and their use in combat conditions was “rare, dangerous and ineffective.” In the Persian Gulf War, as many as 34% of American casualties resulted from their own mines.

Between Law and Pragmatism

The denunciation of the Ottawa Convention by European countries is not merely a strategic move. It is a signal that the boundaries of humanitarian law are ceasing to be self-evident when military pressure mounts. Has Europe entered a new era of “total defense,” in which any tool can be restored to the arsenal?